The Chicken Thief is Never Pardoned

The most common and prosecuted crime of my ancestors may not be a big deal now; but its profound consequences remain

The Chicken Thief and Class Consciousness

In the pre-WWII, it was known as “doing the town.” An experienced thief could steal hundreds of chickens in a year. In June, 1891, the worst chicken thief in Georgia was caught. Five bullets had been fired at him, three hit him but did not kill him; so he was taken to jail. It was reported that he had stolen over 10,000 chickens. “He has raised more chickens than Hages,” the police chief said. (Daily Times-Enterprise, June 6, 1891)

One notorious thief was caught in 1912. He had collected 40 wounds from bullets and dog bites from all his years of thieving, but he was still alive. Another notorious thief was shot after years and years of thieving. He had bird shot in his digestive system from another shooting. It seemed to justify his killing. (Dahlonega Nugget, July 26, 1912)

Not many men ever got rich stealing chickens, but that didn’t stop them from trying. After all, “a bird in the hand is worth two in the coop.” Yet to a poor farmer, the loss of his chickens was a sizable loss to his net worth. To a yeoman or subsistence farmer, it was a big deal to lose a few chickens, perhaps the biggest legal and criminal concern he ever had.

Catching chicken thieves became a sport for some farmers. In one instance, a farmer sat in the bushes by his coop until 1 AM when he saw a man approaching the coop. The farmer said he called for the man to halt. The man made a motion. The farmer said he didn’t know if the man might have a gun. So the farmer shot first. The suspected thief was hit in the side, and suffered great agony for two hours until he expired later that night. The farmer’s action met with general approval. He did what he had to do and there was one less thief for everyone to deal with.

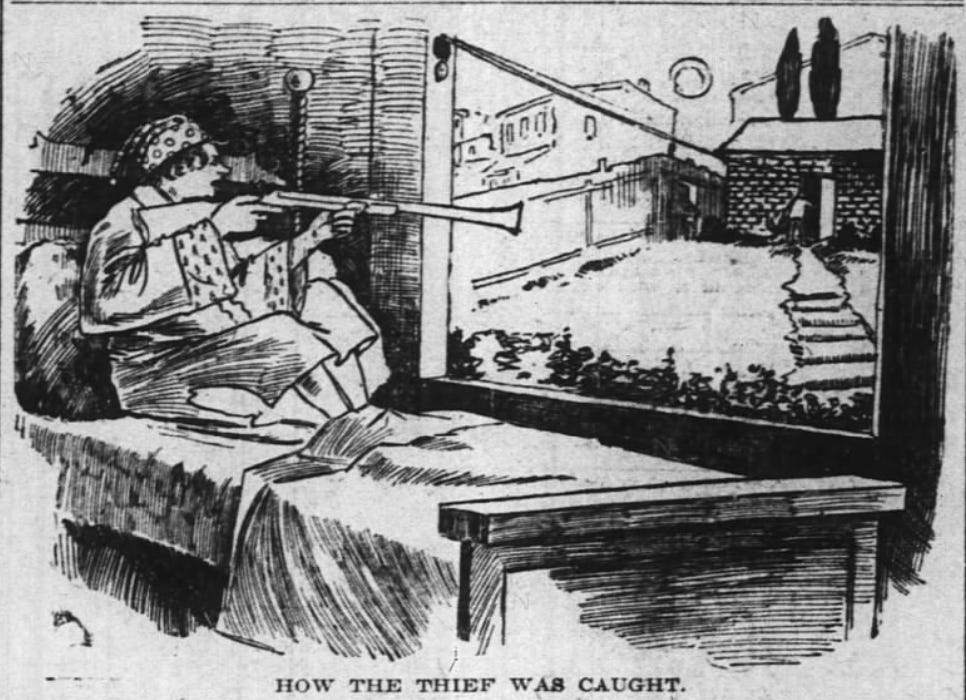

Chicken thieves were generally shot with shot guns, and injured but not killed. On the other hand, one man shot at a thief repeatedly with a rifle, almost killing a sleeping man in another house. One lady shot at a thief with a .38 calibre pistol. “I would freely give $20 in gold if I had only shot that [thief].” (Atlanta Georgian, July 14, 1906 p3)

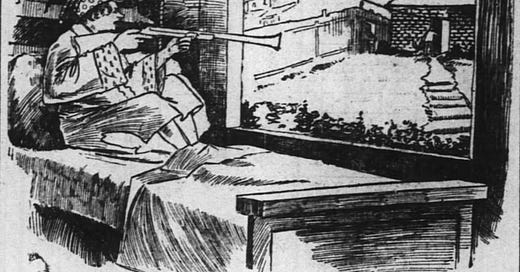

Such a common problem produced a market of contraptions to assist farmers. Trap guns were a common solution. These booby traps were set up by farmers so that when a door to the coop was opened, it triggered a gun or explosive, usually by some connected wire. Woe to the thief or anyone in the way of the gun when it fired or misfired. One farmer found a thumb in his trap the morning after an attempted theft. (North Georgia Citizen, May 20, 1880 p2)

There seem to be more stories of these trap guns killing the person setting the gun than any criminal. Many men died this way. (Dahlonega Nugget, Nov 17, 1922)

The killer did not face consequence for these homicides, unless he shot the wrong person. One Gainesville man killed his brother in 1909 after thinking he was a thief. In fact, he was walking down the street with chickens he had purchased.

Since stealing occurred at night, without witnesses, there was almost always a burden to police and prosecuting attorney to put forward a convincing, but circumstantial case. It was also true that the alleged chicken thief was often not the true culprit. Thus, there could be a lot of he said/they said, making the jury work hard in deliberation and sorting out the truth.

The courts were cluttered with accused chicken thieves that wanted their day in court. The court system moved more swiftly then; for instance a court could have two murder jury trials on the same day, and still do other business. Still, trial days were limited and a judge and jury could spend all day trying a chicken thief. In most of the state of Georgia, there was only one judge that rode the circuit of multiple counties.

In the early 1900’s, it was a common complaint about how much time courts spent on this petty crime. “A … chicken thief is just as liable to engage the entire machinery of the Superior Court for a day as of any felony case, and cost the people of the county just as much as if his offense consisted of a diabolical crime.” (Cedartown Standard, Oct 24, 1901 p2)

Also, at least to the merchant class, town dweller, it seemed chicken thieves were punished more severely than bank robbers. “If it had been some poor, old, ignorant [man], and he had come into possession of a hen and chickens, or a pot, by some mysterious hook or crook, it would have been called theft, and he would have had to work it out on on the road as an example to others…. on the other hand, if it had involved millions, they would be sent to federal prison for a year or so as … and it would be called ‘graft.” (Cedartown Standard, October 31, 1918, p7)

Alas, these townspeople didn’t see the importance of losing a few chickens, or the threat that came from having thieving neighbors. If a thief would steal a man’s livelihood, if a neighbor couldn’t be trusted, then what else may happen?

Most convicted chicken thieves were sentenced to 6 months in the chain gang, 30 days in jail or $50 in fines. But as described earlier, conviction wasn’t necessary to punish a suspected thief. It was a fact that “the chicken thief is never pardoned.”

The culture of that time and place had accepted that to kill a certain type of chicken thief was not a criminal offense; it was an acceptable way of dealing with a petty crime. In fact, sometimes if a man was shot accidentally, the shooter would accuse him of being a chicken thief just to escape punishment. (Cherokee Advance, September 2, 1905)

Merchants and townspeople certainly frowned on what was going on. They saw this as disproportional. Yet it was inevitable, not a hill to die on. Their neighbors and customers out in the country needed violent self-help to handle the situation, and society gave them that margin.

Consistently, what the farmers lacked in social and cultural capital, they made up in sheer percentage of the voting public. Thus, the sheriff and judge and solicitor listened and spent a disproportionate amount of time tracking and prosecuting chicken thieves. Likewise, the police knew that if they didn’t punish the chicken thief, farmers would take matters into their own hands.

As with most things in this category, there was a significant racial element with chicken thieving and how it was handled. Besides the accidental shootings, every story told above involved the shooting of a black man.